|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Non-Tornado Training Page

Examples of tornado look-alikes and illusions which were not tornadoes.Almost as important as identifying a tornado, is being able to identify a "non-tornado".

| |

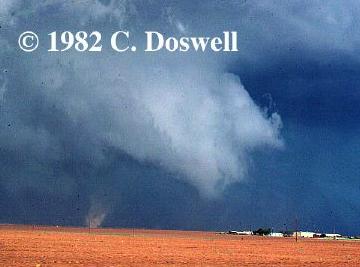

Precipitation shaftThere is a strongly rotating, well-developed mesocyclone and wall cloud in this video frame. But the dense formation connecting cloud to ground was actually a shaft of rain and hail! In real-time motion, the precipitation shaft was slowly rotating as it cascaded downward toward the ground. To the credit of spotters in the area, it fooled nobody and was not reported as a tornado. |

| |

Precipitation shaftIt looks like there could be a partly rain-wrapped, front-lit tornado crossing the road in the distance. Instead, sunlight filtered through a break in the clouds, illuminating a relatively intense part of a precipitation core. In such a situation, the spotter should watch for evidence of rotation in the feature, and also debris or power flashes at the bottom. Neither happened here. |

| |

Precipitation shaftThis rain shaft was thin but intense as it descended from cloud base; but dispersed somewhat while falling. Superimposed on lighter ambient rain cores, a feature like this may fool an untrained or inexperienced spotter, at least temporarily. Again, they key is to watch for rotation. |

| |

Precipitation shaftWhen a dense, narrow precip shaft falls directly through the center of a supercell's circular cloud base, it can mean trouble for both the updraft and for spotters -- who may be fooled into reporting a tornado. This is especially true at long distances when the observer is too far away to determine whether the feature is rotating. In such cases, it is probably best to report a "suspicious lowering." |

| |

Precipitation coreA very dense rain core with an apparent clear slot in the foreground cloud base. This looked like a partly rain-wapped "wedge" tornado and was very deceptive. Veteran storm observer Tim Marshall reported, "Yes, I even had to blink twice." As with the other scenes, though, there was no rotation. |

| |

DownburstThis video snapshot, from many miles away, zooms in to a downburst with a very intense precipitation core at its heart. The flared bottom is not a rotating, tornadic debris cloud, but instead, rain and dust lofted skyward around the edge of the downdraft. The observers had to study this feature carefully for a few minutes, suppressing their initial excitement that this could be a "wedge" tornado, until it was obvious the lowering was not rotating. Distance increases the potential for spotters and chasers to misdiagnose something like this. |

| |

Precipitation coreHere is a pseudo "wedge" -- possibly a convincing mimic on a day where the ambient weather conditions and the structure and evolution of this storm did not favor production of large "wedge" tornadoes. Even for the spotter who has little forecasting understanding or experience, careful watching of this feature for a minute or two, before jumping to hasty conclusions, should reveal its non-tornadic nature. Still, some cores which look like this may produce extreme wind or hail, or if associated with a mesocyclone, may contain a smaller, rain-wrapped tornado. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudSeeing the formation in this 35 mm snapshot, the photographer recognized that it wasn't a tornado but feared that other spotters would report it as one. Not 5 minutes later, it happened: A tornado warning came over the weather radio for its location based on "several spotter reports of a tornado." It was actually a large, low-hanging, non-rotating cloud chunk along an inflow/outflow interface in the distance, whose base-to-ground gap was obscured by a thin layer of outflow dust in the foreground. Multiple spotters apparently didn't notice that this thing was not rotating, leading to a false-alarm tornado warning. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudThis video frame shows a low chunk of cloud material along the leading edge of outflow from a supercell's precipitation core. It was not rotating...only rising with the lift provided by the cold outflow air. This was the same process as what produced the non-tornado in the previous image, but without the foreground dust to obscure the bottom. Even the shape is similar (albeit slimmer), with the flared base and curved tilt. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudHere is another photograph of a tilted, low-hanging protuberance along the edge of outflow. After seeing the previous two images, this one may be easier to interpret; but out in the field, this feature very briefly tricked even experienced NSSL scientists. It is critical for every storm observer to be familiar with concepts like inflow, outflow, mesocyclones and how they relate to visual storm structure. This way, when presented with suspicious, low-contrast and partially rain-obscured features like this, one can make the correct call...here, a non-tornado. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudThe outflow process which caused this false tornado is the same as in the previous three pictures, but reversed in view, with the outflow-producing core at right and rear. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudDespite its ominous appearance, this lowering was not rotating. In fact, instead of threatening to produce a tornado, the storm soon would blow out huge amounts of cold outflow and die. Distance and terrain -- two common handicaps in storm spotting -- obscured the bottom of this feature. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudLooking W just after sunset, this lowered cloud base was in the southern flank of a storm which did have mid level rotation indicated on radar. The bottom of the lowering, which was not rotating according to closeby observers, was obscured from view by houses and trees on the distant hilltop. This illustrates the difficulty of spotting in cities and towns, and the need for a cautious, continual observation of suspicious features in the distance. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudThe observer knew better, but in situations like this where there is low light and poor contrast, some spotters might hastily judge this harmless low cloud to be a funnel or tornado. It was not rotating. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudOutflow winds from the core at right undercut a real wall cloud and created non-rotating scud beneath it. Because of distance, obscuring terrain, and the presence of a legitimately threatening cloud formation above, such harmless scud easily could be reported as a tornado. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudFor a few minutes, the photographer looked east and watched this non-rotating, very low-hanging scud mass take on a smooth tornado-like appearance, here shown as it moved behind a hill and a farm. For many observers, further confusion may result from the presence of this feature under a vigorous updraft base -- where legitimately tornadic circulations also may occur. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudThere is no tornado or wall cloud in this photo. Instead, the suspicious lowering is a large, harmless scud mass dangling from the ambient storm base. It was actually in the outflow region behind the narrow shelf cloud visible in the foreground. The hill elevates the visual horizon and give the illusion that the cloud is on the ground. When spotting, and if possible, it is best to find vantages where there are no hills, tree stands, buildings or other obstructions preventing view of the ground under the cloud base. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudThere may not be a more deceptive non-tornado picture than this. The feature consisted of a large amount of scud -- some of it in apparent contact with the ground -- along the edge of a rain core and under a lowered cloud base. Within 10 minutes, an arcus cloud became better defined above (next photo), with the low clouds still having a tornado-like appearance. Amazingly, no tornado reports happened despite the potential for this to fool many spotters. There was never rotation or violent motion of any kind. The feature moved across parts of western Denver as part of a gust front, with no damage reported. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudThis is a wide angle view of the same feature in the last photo, but 10 minutes later. Understanding storm structure and evolution is probably the most important part of storm observing, as underscored here. With a wide view and several minutes of keen observation in person, the "Denver Fakenado" was shown to be an outflow formation, despite its ominous appearance. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudTo the seasoned storm observer, this is obviously a pile of scud under an arcus cloud, associated with a gust front flowing out of the precipitation core at right. Such features are sometimes mistakenly reported as tornadoes, however, by inexperienced or over-eager spotters. The process here is basically the same as in the much fatter non-tornado in the last picture. |

| |

Non-rotating low cloudLegitimate tornadoes and funnel clouds had been reported elsewhere in the region on this day, and this one easily could have been mistaken for a tornado under such circumstances. Instead, here was a case where the spotter showed due restraint and watched closely for signs of rotation. This cloud feature, as in the previous picture, was formed from ground level by cold, moist, outflow air. The scud was not rotating -- just rising -- and produced no damage. This feature, correctly, was not logged as a tornado. |

| |

Gustnado and separate non-rotating low cloudThere is no tornado or wall cloud in this photo either. The dust whirl at lower right was a gustnado out over the nearby field -- a whirlwind which spins up along an outflow boundary. It was well in front of the background cloud lowering, which might not be apparent in this 2-dimensional image, but which an observer should notice. The important spotting concept in this whole scene is ground-to-cloud continuity. In other words, does the little vortex on the ground have a counterpart above it in the cloud base? No. Gustnado vortices do not extend into the thunderstorm's cloud base, and are therefore not tornadoes. Still, they are frequently mis-reported as tornadoes -- sometimes even in official local storm reports (LSRs). As in the last photo, the cloud lowering was a harmless mass condensing along and above outflow -- near an elevated inflow/outflow interface. It had no debris beneath, and more importantly, was not rotating. |

| |

Shadow IllusionFor a spotter hastily thinking "tornado," the scene in this photograph would be an optical illusion. It was actually an upward-directed shadow, cast on a higher cloud deck by a low cloud eclipsing the setting sun. This picture illustrates well the potential for error when spotting amidst buildings and trees -- where the tell-tale parts of the view are obscured. |

| |

Tail CloudIn this HP (high-precipitation) supercell, the center of rotation was actually above and slightly to the left of the fence post, near the right edge of the dense precipitation core. There was no tornado at the time of this picture. The low-hanging, tapering feature at right is called a tail cloud, and is an inflow feature. A tail clouds often forms between the low level mesocyclone (left and center) and the forward-flank core (far right). It condenses below the level of the main cloud base as a channel of rain-cooled air from the core is drawn upward into the rotating updraft. Tail clouds sometimes have very fast, horizontally tilted rising motions. Because they can hang so low, taper like a funnel, and contain rapid cloud movement, they are sometimes mistaken for tornadoes. The key with suspicious cloud features is to look for rapid rotation, and evidence of spinning debris under the cloud base. |

| |

"Smokenado"Tornadoes don't come from pure stratus, despite what was depicted at times in a popular Hollywood movie about the subject; yet a scene like this might trick an inexperienced observer. This was a transportation-camera video capture of a smoke plume rising into stratus, and spreading out just below ambient cloud base. That spreading of the ragged smoke plume gives an illusion of a wall cloud surrounding the "smokenado." Image courtesy Minnesota DOT and NWS Minneapolis. |

| |

"Smokenado"This is one of the most infamous non-tornadoes among storm enthusiasts. The "Nova" PBS special on storm chasing, filmed in 1985, prominently included footage of a smoke column rising into a weakly rotating cloud base, along with NSSL storm intercept crew members mistakenly yelling, "tornado." This is a 35 mm slide of the "smokenado" which fooled so many experienced storm observers back then. |

| |

"Smokenado"A fine example of a smoke column extending from ground to cloud base, this time along a gust front. Note the strong resemblance between this and the photo above, despite being in two different storm situations, 16 years apart. If the spotter knows the storm is outflow-dominant and cold air is surging from it, this is little more than a harmless curiosity. To the inexperienced or poorly positioned observer, however, it might seem far more alarming than it should. |

So remember... ROTATION ROTATION ROTATION!

Back to The Spotters Page